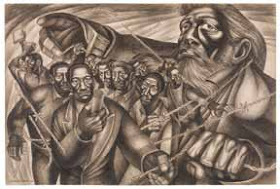

African American Artist: Charles W. White, Jr.

Frustrated by the education system’s omission of Black contributions to American society, White, out of this frustration, began to skip school. At age 14, he worked as a sign letterer for the Regal Theater, where he began meeting other Black artists. He worked with George E. Neal, a Black artist, who while supporting himself by lettering and illustrating small Black publications, studied at the Art Institute. White’s drawings won a competition, permitting him to attend a Saturday “honors” class at the Art Institute. Artists Charles Sebree and Margaret Burroughs also attended this class.

“He was a particularly inspiring teacher,” said White, referring to Neal. “We used to have classes in his home. Elzier Cortor, Charles Sebree, and Frank Neal, who wasn’t related to him, as well as me, were all influenced by George. He made us conscious of the craft aspect of painting technique. He made us conscious of the beauty of those beat-up old shacks. He made us conscious of the beauty of Black people.”

When he was 16-years-old, White attended a Saturday night party at the studio of Katherine Dunham, then a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Chicago and developing her dance career. There he met poet Gwendolyn Brooks, author Margaret Walker, Richard Wright and Willard Motley; sociologist Horace Cayton; and many other artists and intellectuals gathering on Chicago’s South Side. He was exposed to many new ideas. They could be described as Alain Locke’s “New Negro,” a philosophy that would have a great impact on White.

White won a scholarship to study at the Art Institute full-time. He also began to work as a Works in Progress (WPA) artist and became a member of the Arts and Crafts Guilds. At the Art Institute, White was introduced to the Mexican muralists who used art to educate the masses. This concept greatly excited White, as it would excite the artist Elizabeth Catlett, whom he would later marry. He wanted his art to speak to Black people, instilling and reaffirming confidence and pride.

White met and married talented sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, who then taught at Dillard University in New Orleans and was taking the summer to study at the Art Institute. He had won two scholarships, one to the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts and the Frederic Mizes Academy of Arts, both of which were withdrawn upon the discovery that White was actually Black.

White would later win a Julius Rosenwald Foundation study grant to do research in the South. In the South, White began to understand the beauty of the “Negro” speech, folklore and poetry, dance and music. The music especially moved him — the spirituals, blues, ballads, the work songs. This music had a very profound meaning for White and his work.

Two racially motivated events, to occur later, would also have profound effect on White. First, he was severely beaten for entering a restaurant in New Orleans. Secondly, in Hampton, Virginia, a conductor forced White to the rear of a streetcar at gunpoint. Over the course of 15 years, he would learn of the lynching of three uncles and two cousins. White developed an anger against injustice that deepened.

White and Catlett would eventually moved to New York, where the painter Ernest Crichlow introduced them to Black artists and intellectuals. Catlett began studies with the Cubist-influenced sculpture Ossip Zadkine. White studied with Harry Sternberg, a leading instructor of etching and lithography at the Art Student League.

White and Catlett would leave New York to teach at Hampton Institute in Virginia until White was drafted in 1943. Soon after, White developed tuberculosis. He spent three years in a Veterans hospital in Beacon, New York. White did not paint during this time. He devised his own therapy. He reread all that he had read during his adolescence.

Upon recovery, he returned to New York and created. He had a one man show at the American Contemporary Artists (ACA) Gallery in September 1947. That fall, White and Catlett went to Mexico at the invitation of the famous muralist David Siquerios. They studied and worked at Mexico’s famous graphic workshop Taller de Grafica Popular for nearly a year.

“I saw artists working to create an art about and for the people,” said White of his Mexican experience. “This has been the strongest influence in my whole approach. It clarified the direction in which I wanted to move.”

His marriage to Catlett ended soon after his travels to Mexico. His health began to deteriorate again. He was hospitalized for a year in New York where he was to undergo lung surgery. White’s art began to gradually shift from historical figures to ordinary common Black folks, always maintaining the same dignity. His work became more rhythmic and fluid, realistic and humanistic.

In 1950, White married Frances Barrett. They honeymooned in Europe and were delighted to find that White’s lithographs received high recognition. Portfolios of his work could be found throughout Europe. Upon returning to the U.S., White’s failing health prompted the newlyweds to move to California for the weather. In California, he gradually regained his health.

White’s works were being discovered by the Black Consciousness movement of the 1960s. Black colleges anxiously sought his exhibitions. The socially conscious artists of the 1930s were finding new eyes in the 1960s.

Charles White, Jr. died in 1980. It was he who best articulated his art. “I use Negro subject matter because Negroes are closest to me. But I am trying to express a universal feeling through them, a meaning for all men… All my life, I’ve been painting a simple painting. This does not mean that I am a man without anger — I’ve had my work in museum’s where I wasn’t allowed to see it. But what I pour into my work is the challenge of how beautiful life can be.”

Adapted from article originally published in “Afrique”; Charles White: The Art of a Chicago Son Beautifies Experiences of Common Black Folk; Cross, Vanessa; June 1996

A Dedication

A Dedication